Sheikh Rami Nsour is a traditionally trained instructor of the Islamic sciences, who has spent many years under the tutelage of Mauritanian scholars both abroad and in his native USA. However, a chance encounter with a former prison inmate in 2002 set him on a journey that eventually led to the establishment of Tayba Foundation, a leading Islamic organisation that provides traditional Islamic education within the US prison system. Sheikh Rami is currently the founding director of the Tayba. We had the opportunity to sit down for a chat with him and had an interesting conversation covering issues such as the popularity of Islam within the prison population, the day to day operations of Tayba and also the Islamic rationale in dealing with the incarcerated...

You have been teaching in prisons for quite a while, how did you get into this?

I started in 2002, and what happened was there was a brother who came to Zaytuna institute in California and this brother was released from prison and he had been following some of the publications of Zaytuna. We met him and he had some questions from some brothers in prison and asked if we minded answering them. I said sure. I thought they were going to be very basic, but they turned out to be very specific questions. I said to myself a person with this capability should have some tutoring and so I started teaching one prisoner by phone. He would call me, I would send him the material and the books we were going to be going over and that led me to take on ten more students over the next couple of years. Eventually, in 2008 we expanded and I established a non-profit, it then became 150 [students] and now we are at 1800 registered students Alhamdulillah.

1. Founding members Shaykh Rami Nsour (left) and Nabil Afifi (right)

Why do you think Islam is so popular within the prison system?

Islam is growing in prisons on its own, so we don’t do any dawah work or proselytising per se, that’s happening on its own. People are coming to Islam, people are becoming Muslims. But what we do is when people become Muslim, that is when we are set up to provide education for them.

In the prison setting, one of the things that occur is that the Muslims have a significant presence within the prisons. There is an element of respect that the Muslims have had over the last fifty years in the US prison system. That’s from things like being on the forefront of fighting for prisoner rights and filing lawsuits. Just a while ago, one of our students won the right for halal meat for the entire state of Colorado. So the prisoners get into the law libraries and they do this work and they have gained a lot of respect within the prison population for that. Then also the discipline they have and the protection that they offer as well (the Muslims amongst themselves). So sometimes people gravitate towards the Muslims because they are looking for the father figure, they are looking for protection, that’s one element.

Then you’ve got the other people, who once they are in prison they are taken out of their societies. I mean the gangs are still there, the drugs are still there to a certain extent, there is still alcohol, there is still gambling and there still is prostitution, but it’s a lot less than what is on the streets. A lot of people now have the time to sit there and reflect, and once they start reflecting they start looking into the racism, they start looking into oppression, they start looking into intergenerational poverty, institutional racism, government policies, and also slavery. For a lot of people, especially in the African-American communities, that then leads them to West Africa. West Africa which of course is Islam, they learn about Islam, they see all the history about the impact of Islam, the story of Malcolm X for example, there are a lot of factors that would influence them on their journey. Whatever the factors may be, whether it’s the respect they have gained or the spiritual searches that people are on Islam is the fastest-growing religion in the prisons.

How many states are you currently operating in?

Right now it's 30 of the 50 states. So we have students out of at least thirty states in both state and federal prisons. We have students who have registered from 120 different facilities both state and federal.

How is such a large number of students organised, how does the setup work?

Most of our education right now is done via distance or correspondence, so we have a syllabus with books.

We used to have a book attached with a CD which we would send to the prisoner and then they would listen to the CD, or they would watch the DVD and then they would send us in questions, answers, projects and essays etc. But now we have everything self-contained in one book, so there is an audio component which has been transcribed when they get the book they will have a syllabus and an exam.

So they will receive this book, and we ‘pack’ it because we know the students have a lot of time to read and also they often aren’t able to interact with us. They can send us a letter but we have to read the letter, process the question and then send it back so there is this lag between the time they ask the question and the time they get a response. What we try and do is that as these questions come in we keep putting them back in the curriculum so that the course becomes thicker and thicker and gives them more reading material so that we are answering the majority of questions before they even have to contact us. We give them a lot of material; we make sure it's digestible and we try to answer as many questions as we think may come up in that subject, they read through that material, they send us their essays and projects, we grade it and then they start on the next course.

So, we don’t really need to do any advertising in the prison, in 2009 we advertised our programme in the prisons and that’s where we grew our students but from that time it has spread through word of mouth.

Are there any instances where you are able to gain authorisation to teach within the prisons?

I’ve been to a few prisons and I’ve done a couple of lectures and seminars but what we decided as an organisation was that there is no doubt that having an in-person teacher is the best thing. The next best thing is to have somebody that you can actually talk to by phone, and then the next best thing is to have somebody you can correspond with via email or written correspondence and then the next best thing is to have somebody who is giving you a book, grading your essays and answering your questions. So we know it's not the optimum form of teaching but we work on a very limited budget. If we want to use that budget to support teachers and to actually go into prisons it takes a long time to get security clearance for each facility and sometimes you have to do it for each visit.

The second thing is that a lot of the prisons are located in remote areas so if I was to try and go to prisons it would be very difficult and very limited. Once I get to the prison, say you have a prison population of 100 Muslims, well there may be 100 Muslims in the prisons but maybe only 75 of them are actually coming to the Jumu'ah services or are coming to the Chaplain and from those 75 maybe its only about twenty that are actually regularly praying five times a day, and from that twenty maybe it's only about five who are serious students.

So what we decided was rather than spend our limited resources going in-person to prison and only ending up benefiting those five or so people, if we use the distant platform we can get those five students (for example's sake) out every state all over the US. So, we are connected to all those students who they themselves are the ones leading prayers, they are the ones leading halaqa's and giving advice, they are the ones essentially acting as the Imams or Chaplains in the absence of a Muslim Imam. So, for us providing those men and women with resources they can then turn around and teach the remainder of the congregation. But our vision in the future, where I would like our organisation to be in twenty years is that we would have an Imam supported by Tayba that is going into those prisons.

What has been the response of the prison staff in regards to your work and have there been comments on the effect it has had on the inmates?

Most of what we get in terms of comments is thanking us for being part of providing materials and doing something for the prison. There are some people who will thank us for the content and the transformative effect that it has but most of the thanks come from people thanking us for being a member of the society that is sending in educational resources to prisoners regardless of what it is.

In one case we did have some commissioners provide feedback. One of the things that happens for the ‘lifers’ (a person serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole) is that when they come up for ‘review’ the board of commissioner’s review the prisoner's case and decide whether they are fit to go back into society. In order for the prisoner to prove their case, they will come with a whole stack of evidence proving that they have changed. So, they may have certificates of completion from narcotics anonymous meetings, alcoholics anonymous, gang rehabilitation programmes and such things. For our students at Tayba, we will also send them a letter and we will say “this person has been involved in our programme for this many years and we feel he has changed as a person and we recommend he should be released”. So, as they are reviewing these things one of the comments we have heard is that they have noticed prisoners coming up for parole hearings who have Tayba foundation letters all have a similar quality, they have actually changed and they can actually see that the common denominator between these Muslims is that they are also Tayba foundation students. Now, we are not going to make a claim that our education changed those people, we just enhance the change that is already happening, so we have definitely helped and changed people but there was already a process of change going on with those men and women.

Some may say why take the time out to deal with prisoners? Is there an Islamic requirement to look after them?

Yes, it’s in the Quran. If we were speaking to the general public if we were going to look at it from a philosophical standpoint one of the things that Dostoyevsky says in his book Crime and Punishment is that you judge a society based on how they treat their criminals. If you think about that it’s very profound because these are the people who are the worst of your society, they have killed, maimed, raped, robbed and abused. Whatever it maybe they have done everything, as a society how do we treat that person? Dostoyevsky is only from the last hundred and fifty years or so but if we look at our tradition we find in the Quran that after the battle of Badr one of the Ayahs that was revealed was to feed the prisoners and Allah SWT says ‘And they give food in spite of love for it to the needy, the orphan, and the captive’ and he put them all in the same category so you are not going to have trouble finding funding and getting donations to feed the poor and you’re definitely not going to find any trouble feeding orphans right? But the prisoners are right there in the same category.

So, you can see how prisoners can easily be squeezed by the society so when the Muslim took the prisoners at the time of Badr the Prophet (ﷺ) gave them specific examples he said to treat them as your guests, you feed them your best food and you feed them before you feed yourself. These prisoners of war at that time what did they do? They had come out to kill the prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) and his Sahabah. So, if these people are who Allah is telling us to feed, and Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) is telling them to feed them the best food, and treat them as guests and maintaining the humanity of these people. That’s what I would say, the foundation for us as Muslims and even for people in the west is we have to maintain the humanity of the prisoners it doesn’t mean we become gullible and we don’t address the crimes. As Muslims it doesn’t mean we don’t agree with the death penalty at the times that it is required, it doesn’t mean we don’t agree with an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth but it also doesn’t mean we have to torture these people or remove their humanity from themselves. At the base of it, whether it’s the Islamic tradition or any other tradition it is about maintaining the humanity of people.

The second thing that I would say is that as Muslims we also recognise that most prisons systems are unjust and the US is no exception to that, we house the most prisoners in comparison to any other country, 22% of the world's prisoners are in the US and the overwhelming majority are minorities. So, we have poor and minority ethnicities in the prison system so we know it's an unjust system. I know one person who at 17 years old was given three life sentences for having a quarter gramme of crack cocaine. Afterwards, he eventually got out of prison but he served 22 years out of that sentence. In comparison, the Stanford rapist gets 3 months? This isn’t even an anomaly we hear stories like that over and over again. There are people who have been in solitary confinement for 30 years, can you imagine? In a concrete box that is six feet by eight feet and you have your toilet and your sink and you are in that concrete box 23 and a half hours a day. You get half an hour to go into a bigger concrete box to walk around like a rat and that’s considered justice? So for us when we hear anti-Muslims criticise our Shariah we say, hold on one second, on what moral ground do you stand on?

As Muslims, we have our theological standpoint as to why we serve the prisoner. It also reminds us not only of humanity but also about the power of Tawbah (repentance). One of the examples I give is if you had somebody right now in this day and age who killed a number of Muslims, and then he walked into a masjid and became a Muslim how accepting of him would we be? What did Khalid Ibn Walid do? If Khalid Ibn Walid was in the US justice system, he would be in prison right now for what he did right? Umar Ibn al-Khattab what did he do? He buried his daughter, he would be in prison. So just because a person went to prison it doesn’t mean we should automatically consider them a different category. There were Sahabah who before they became Muslims, had committed crimes, they were criminals and then they became Muslims. But we don’t look at them like ‘Khalid Ibn Waleed the criminal’ or the ‘convict who got away’. But when we mention these people we say RadhiAllahu 'anhum! Because we use those stories as magnificent stories of the power of tawbah, the power of change and the forgiveness of Allah. Yet, when we shift it to the prisons all of a sudden we have a different interaction. So, we as Muslims, we have the order from Allah to feed and take care of the prisoner (even if they don’t make tawbah) and then we are reminded that they can make tawbah and then the third thing is that these are people who are going to be coming back to our society so wouldn’t you want them to be reformed?

Do you believe that prisons can sometimes be an incubator for good?

I have heard people tell me that “as bad as prison is, I got Islam through the prison and if I didn’t come to prison I would probably be one of those statistics.” So, yes this is a sentiment that is recognised, prisoners recognise the harshness of their existence in prison but at the same time they know that this prison created a time for them to start thinking, because when they are on the streets and living that life of crime they never have that time to sit down and reflect, it’s always one thing after another and even if they do have time to think it’s not really an environment that’s conducive but when they get into prisons it is a sanctuary or as you said an incubator.

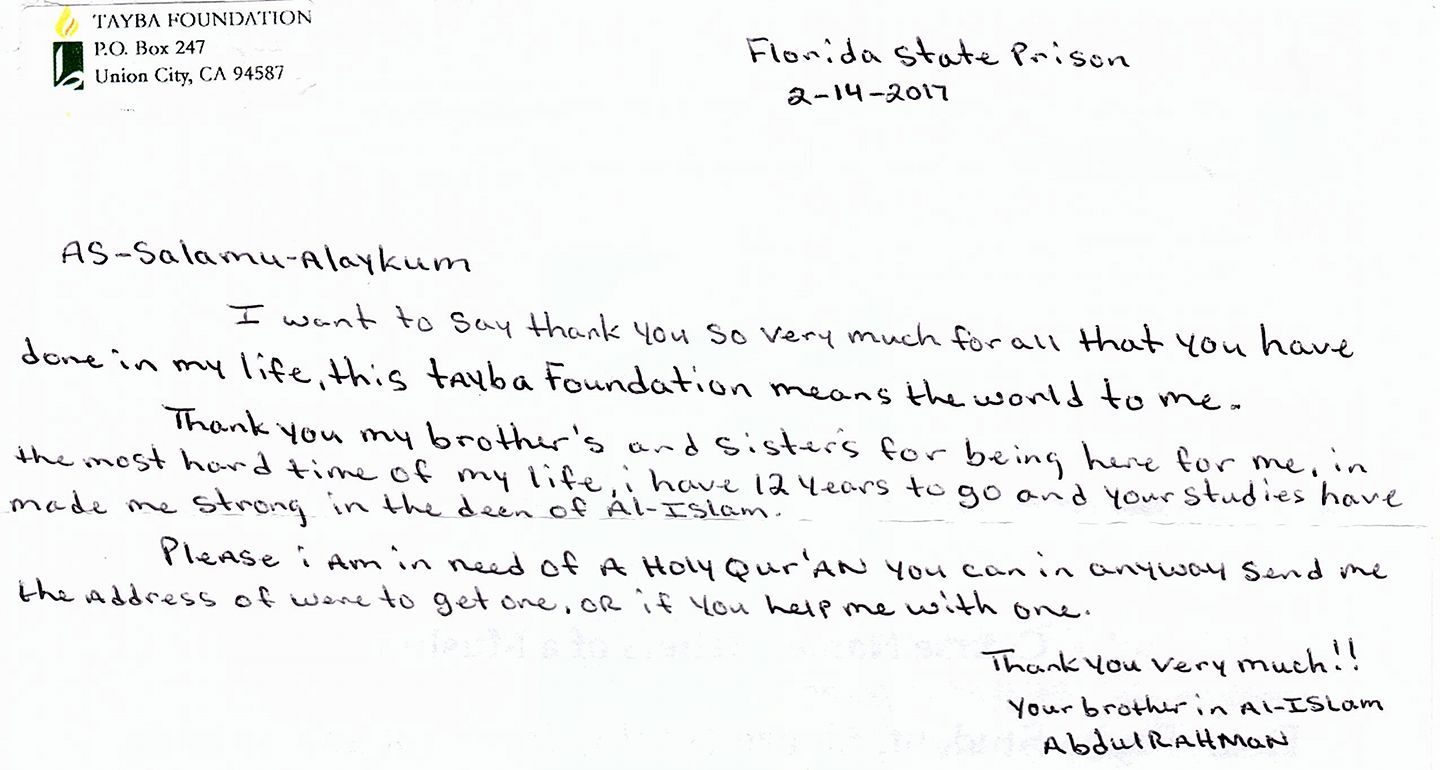

A letter from an inmate in Florida

Do you have a standout example of a student who came through the Tayba foundation?

We have a lot of standout stories, a lot of them can be found on our website. One student, as I previously mentioned, had spent 22 years in prison for a quarter-gram of crack cocaine. He got out of prison, started working for Tayba foundation, he then transitioned into a full-time position as a director of one of the largest Islamic centres in southern California. That’s a big trust that the community put on his hands, this was a person that I vouched for, I said this was a man who was very trustworthy so don’t look at his criminal background and judge him to not be worthy of taking on this position. I recommended him for the position he’s now married to a sister within that community who already had five children previously, so he now has five stepchildren and his own child and he’s taking care of a large family which is a huge commitment. He is involved in national projects in regards to the fair sentencing of youth as well as teen mentoring in mosques. He is doing a lot of work.

Because the other thing for us is that there are a lot of Muslims that we allow in the community to operate even though they have committed crimes but just haven’t been caught for it. Say for example if somebody is a liquor store owner we look at that as a crime if somebody is involved in the banking industry for us to be involved in the riba (usury) industry is a crime. It’s just that this society hasn’t deemed alcohol and interest as a crime, yet those people are allowed to work and be a part of our communities.

We also have our stories of people who come out of prison and then go back. We are learning from both sides we are learning from the successes and also from our students who get back into the drugs, alcohol, womanising and so forth.

You are raising funds for Tayba, what does the money go towards and how will this help?

The majority of the funds go towards the staff, to be able to have teachers and staff to support the students when they write questions or need their papers graded. Right now we have me and four other teachers working part-time and full-time so we have that as well as administrative staff.

Funds also go towards purchasing and creating material including printing and shipping. We spend a lot of money on postage and printing. But what we can say is that 90% of our donations go towards programming.

Financially, the biggest thing we are looking for right now is monthly contributions so five dollars a month whatever it may be. Whatever a person is able to do, it is better for us to have small sustainable donations from our supporters and we are looking to build our small donations base. The other way people can help us is by learning more about what we do and sharing it on social media amongst their friends. If people are interested they can become remote volunteers, we have volunteers from all over the world and we have a team of over 20 volunteers and there are a lot of different projects that we have going on.

The Tayba Foundation is a groundbreaking organisation and caters to a community often forgotten by Muslims in the free world. We urge all of our readers to check out the link below and donate what you can to their cause. We pray that Allah SWT puts barakah into their efforts so that they are able to continue this great service to our brothers and sisters behind bars.

www.taybafoundation.org/donate

A beautifully put together documentary on the story of the Tayba foundation can be viewed below